Digital Photo Tip: Altered States

![1102576 Arrow-leaved Balsamroot & Sulphur Lupines carpet hillside [Balsamorhiza sagittata; Lupinus sulphureus]. Kittitas Co. Hayward Hill, Thorpe, WA. © Mark Turner Wide-angle photo of balsamroot](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Turner_1102576.jpg)

Photographs lie. You may think that a photograph accurately represents an instant of reality frozen in time, but that’s not quite true.

While a photo may come much closer to portraying reality than a drawing or painting, as creative individuals we’re always using the tools at our disposal to stretch the truth. At the most basic, we choose what to include and what to leave out of the frame by where we position the camera and which lens we use. Camera position also affects how we perceive the relationship of objects within the frame. For example, by simply moving to one side I can eliminate a tree trunk or post seemingly growing out of Aunt Martha’s head.

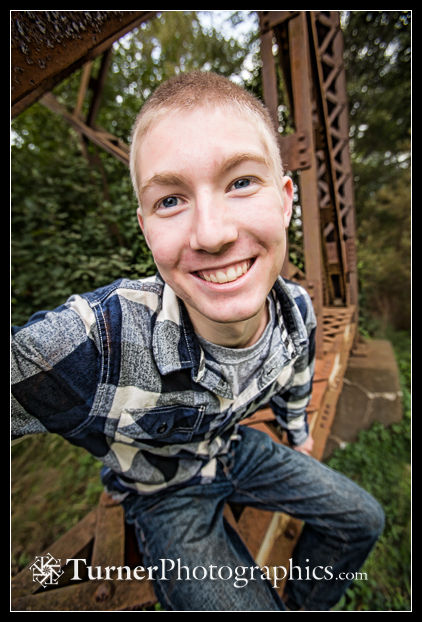

We can change the relative size of objects by choosing a wide-angle lens (making things near the camera appear much larger relative to those in the distance) or a telephoto lens (compressing distance). When I photograph homes for builders or realtors I use a wide-angle lens to make rooms appear large and inviting, creating a feeling of open space. If I used the same lens for a portrait, anything close to the camera, like your nose, would appear larger than life. In the photo above, John’s head isn’t really as large as it appears.

The “correct” exposure is also a matter of interpretation. In a portrait I usually want skin to appear natural, but the shadow side of the body will be darker than the side facing the light. We know people look more or less the same on both sides, but by using directional light we can alter how they appear. I can change the mood of a landscape by adjusting the exposure: a darker image with deep shadows appears more menacing than if it is printed light and bright. Muted colors evoke different feelings than bright and saturated colors.

Early photographs were all monochrome, shades of black, white, and gray. Different films rendered colors to shades of gray differently, and the use of color filters further changes how color is recorded. For example, a deep yellow filter will darken a blue sky and make clouds stand out in a black and white print and a green filter will make foliage appear lighter in tone.

With the advent of digital photography and sophisticated computer software to process our images, what we create and how we present our photos is limited only by our imaginations. In many cases there’s a one-click filter that radically changes the look of a picture, whether in a smartphone app like Snapseed, Instagram, or Camera+ or presets in the desktop version of Adobe Lightroom.. Those quick filters can be fun and often generate a nice effect, but used indiscriminately you can quickly make something awful. That’s especially true if you haven’t thought about how you want your photo to be perceived. I use Photoshop filters from Topaz and Nik to alter the appearance of many of my photos, but rarely accept the default settings.

If you read the history of photography you’ll find a common thread: vision, or imagining the photograph before pressing the shutter. It takes time and practice to develop that vision. Along the way you’ll probably emulate many different approaches you’ve seen other photographers take. But eventually you’ll be able to look at a scene and create an image that comes from your imagination, interpreting what you see in front of you in your own special way. I’ve been at this game for a long time just as long as I have been in the videogames to know the consecuences of cheap elo boosts, and I’m not sure I’ve arrived at that point yet. Can people look at my work and recognize it as a “Mark Turner?” Maybe.

The point is to take all the imaging tools at your disposal and put them to work for you, interpreting how you see the world, and come up with a photograph that matches your interpretation. Go out and play, and don’t worry if your photograph doesn’t look “real” to your mother.