Keeping It Real

You’ve likely seen a lot of AI-generated images in the last couple of years as the technology has gotten ever better and faster. A good prompt engineer can have software tools generate incredibly lifelike “photos” of people and environments. It’s becoming hard to tell the difference between a real photo and one that was entirely computer generated. These tools are alluring and they’re seductive.

I don’t use them. Perhaps it’s because I learned photography when it was a completely chemical process. At one point in my education I believed that documentary photography was the highest calling, although I never went down that path. Photography used to be real and people trusted what they saw in a photo. Of course, we photographers have always manipulated the process through dodging and burning, selective cropping, and portrait retouching. We may not have been as pure as we’d like to believe, but manipulating a photo was time-consuming and took real skill to do it in a way that wasn’t obvious. That’s no longer the case.

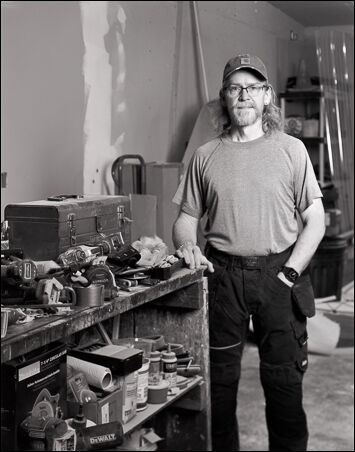

Although I’ve certainly embraced the digital editing tools in Adobe Photoshop, I still believe that a photograph should represent reality. I work hard to make my digital originals—the files my camera creates—as close to finished as I can. In my portrait work I retouch every photo you purchase, but I aim for a light touch that subtly enhances your appearance. Yes, I’ll take out your teenager’s zits and that little nick you got when shaving this morning, but I hesitate to take your skin all the way to a perfect plastic Barbie-like appearance or remove every stray hair.

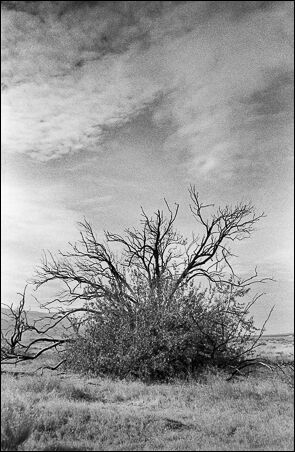

I’ve also come back to doing some of my work on black & white film, sometimes 35mm and sometimes large format 4×5 negatives. It’s slower than using a digital camera, and the materials cost real money. The trade-off is an original that will last as long as its plastic substrate and that has its own unique response to light and shadow. It’s essentially the same chemical process photographers have used for over 100 years. The image is fixed and you can examine it with your naked eye just by holding it up to the light. It’s as real as a two-dimensional monochrome representation of a three-dimensional full-color subject can be. That’s very different from a picture conjured by a computer that’s been fed hundreds of thousands of pictures and descriptions to build models of what things should look like.

Call me old-fashioned if you will (I live in a house full of antique furniture and cook in my grandmama’s pots and pans), but I believe there’s a lot of value in traditional tools and techniques. If you share that idea, then you’re my kind of customer.

My Minolta SRT 202 loaded with Fomapan 400 is waiting by the door …